[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default” custom_padding=”0px||4px|||”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default” width=”76.6%” hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_post_title _builder_version=”4.9.4″ _module_preset=”default” hover_enabled=”0″ author=”off” date=”off” sticky_enabled=”0″][/et_pb_post_title][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”256683de-fd29-4c96-b2ea-2f610e293dd9″][/et_pb_text][et_pb_button button_url=”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF9saW5rX3VybF9wYWdlIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsicG9zdF9pZCI6IjI2In19@” button_text=”Read More” button_alignment=”right” _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _dynamic_attributes=”button_url” _module_preset=”default” custom_button=”on” button_text_color=”#FFFFFF” button_bg_color=”#565656″ button_border_width=”0px” button_border_radius=”14px”][/et_pb_button][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default”]

With apologies to Wikipedia I have taken the liberty here of pasting a section from their entry here :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wells_Fargo

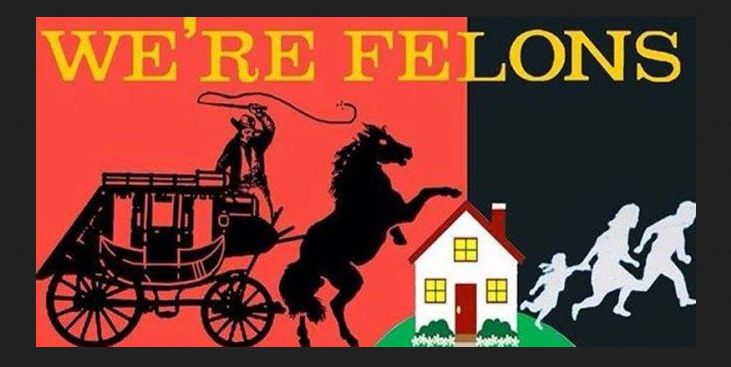

This concerns the history of corruption at Wells Fargo. Few companies that go back in time as far as Wells Fargo can claim to be squeaky clean but surely this list puts Wells Fargo near the top of the pile when it comes to nefarious activities.

****

1981 MAPS Wells Fargo embezzlement scandal

In 1981, it was discovered that a Wells Fargo assistant operations officer, Lloyd Benjamin “Ben” Lewis, had perpetrated one of the largest embezzlements in history, through its Beverly Drive branch. During 1978 – 1981, Lewis had successfully written phony debit and credit receipts to benefit boxing promoters Harold J. Smith (né Ross Eugene Fields) and Sam “Sammie” Marshall, chairman and president, respectively, of Muhammed Ali Professional Sports, Inc. (MAPS), of which Lewis was also listed as a director; Marshall, too, was a former employee of the same Wells Fargo branch as Lewis. In excess of US$300,000 was paid to Lewis, who pled guilty to embezzlement and conspiracy charges in 1981, and testified against his co-conspirators for a reduced five-year sentence.[89] (Boxer Muhammed Ali had received a fee for the use of his name, and had no other involvement with the organization.[90])

Higher costs charged to African-American and Hispanic borrowers

Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan filed suit against Wells Fargo on July 31, 2009, alleging that the bank steers African Americans and Hispanics into high-cost subprime loans. A Wells Fargo spokesman responded that “The policies, systems, and controls we have in place – including in Illinois – ensure race is not a factor…”[91] An affidavit filed in the case stated that loan officers had referred to black mortgage-seekers as “mud people,” and the subprime loans as “ghetto loans.” [92] According to Beth Jacobson, a loan officer at Wells Fargo interviewed for a report in The New York Times, “We just went right after them. Wells Fargo mortgage had an emerging-markets unit that specifically targeted black churches because it figured church leaders had a lot of influence and could convince congregants to take out subprime loans.” The report goes on to present data from the city of Baltimore, where “more than half the properties subject to foreclosure on a Wells Fargo loan from 2005 to 2008 now stand vacant. And 71 percent of those are in predominantly black neighborhoods.”[93] Wells Fargo agreed to pay US$125 million to subprime borrowers and US$50 million in direct down payment assistance in certain areas, for a total of US$175 million.[94][95]

Failure to monitor suspected money laundering

In a March 2010 agreement with US federal prosecutors, Wells Fargo acknowledged that between 2004 and 2007 Wachovia had failed to monitor and report suspected money laundering by narcotics traffickers, including the cash used to buy four planes that shipped a total of 22 tons of cocaine into Mexico.[96]

Overdraft fees

In August 2010, Wells Fargo was fined by US District Court judge William Alsup for overdraft practices designed to “gouge” consumers and “profiteer” at their expense, and for misleading consumers about how the bank processed transactions and assessed overdraft fees.[97][98][99]

Higher costs charged to African-American and Hispanic borrowers[edit]

Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan filed suit against Wells Fargo on July 31, 2009, alleging that the bank steers African Americans and Hispanics into high-cost subprime loans. A Wells Fargo spokesman responded that “The policies, systems, and controls we have in place – including in Illinois – ensure race is not a factor…”[91] An affidavit filed in the case stated that loan officers had referred to black mortgage-seekers as “mud people,” and the subprime loans as “ghetto loans.” [92] According to Beth Jacobson, a loan officer at Wells Fargo interviewed for a report in The New York Times, “We just went right after them. Wells Fargo mortgage had an emerging-markets unit that specifically targeted black churches because it figured church leaders had a lot of influence and could convince congregants to take out subprime loans.” The report goes on to present data from the city of Baltimore, where “more than half the properties subject to foreclosure on a Wells Fargo loan from 2005 to 2008 now stand vacant. And 71 percent of those are in predominantly black neighborhoods.”[93] Wells Fargo agreed to pay US$125 million to subprime borrowers and US$50 million in direct down payment assistance in certain areas, for a total of US$175 million.[94][95]

Failure to monitor suspected money laundering[edit]

In a March 2010 agreement with US federal prosecutors, Wells Fargo acknowledged that between 2004 and 2007 Wachovia had failed to monitor and report suspected money laundering by narcotics traffickers, including the cash used to buy four planes that shipped a total of 22 tons of cocaine into Mexico.[96]

Overdraft fees[edit]

In August 2010, Wells Fargo was fined by US District Court judge William Alsup for overdraft practices designed to “gouge” consumers and “profiteer” at their expense, and for misleading consumers about how the bank processed transactions and assessed overdraft fees.[97][98][99]

Settlement and fines regarding mortgage servicing practices[edit]

On February 9, 2012, it was announced that the five largest mortgage servicers (Ally Financial, Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo) agreed to a settlement with the US Federal Government and 49 states.[100] The settlement, known as the National Mortgage Settlement (NMS), required the servicers to provide about US$26 billion in relief to distressed homeowners and in direct payments to the federal and state governments. This settlement amount makes the NMS the second largest civil settlement in US history, only trailing the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.[101] The five banks were also required to comply with 305 new mortgage servicing standards. Oklahoma held out and agreed to settle with the banks separately.

On April 5, 2012, a federal judge ordered Wells Fargo to pay US$3.1 million in punitive damages over a single loan, one of the largest fines for a bank ever for mortgaging service misconduct.[102] Elizabeth Magner, a federal bankruptcy judge in the Eastern District of Louisiana, cited the bank’s behavior as “highly reprehensible”,[103] stating that Wells Fargo has taken advantage of borrowers who rely on the bank’s accurate calculations. She went on to add, “perhaps more disturbing is Wells Fargo’s refusal to voluntarily correct its errors. It prefers to rely on the ignorance of borrowers or their inability to fund a challenge to its demands, rather than voluntarily relinquish gains obtained through improper accounting methods.”[104]

SEC fine due to inadequate risk disclosures[edit]

On August 14, 2012, Wells Fargo agreed to pay around US$6.5 million to settle US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charges that in 2007 it sold risky mortgage-backed securities without fully realizing their dangers.[105]

Lawsuit by FHA over loan underwriting[edit]

On October 9, 2012, the US Federal Government sued the bank under the False Claims Act at the federal court in Manhattan, New York. The suit alleges that Wells Fargo defrauded the US Federal Housing Administration (FHA) over the past ten years, underwriting over 100,000 FHA backed loans when over half did not qualify for the program. This suit is the third allegation levied against Wells Fargo in 2012.[106]

In October 2012, Wells Fargo was sued by United States Attorney Preet Bharara over questionable mortgage deals.[107]

[edit]

In April 2013, Wells Fargo settled a suit with 24,000 Florida homeowners alongside insurer QBE, in which Wells Fargo was accused of inflating premiums on forced-place insurance.[108]

Lawsuit regarding excessive overdraft fees[edit]

In May 2013, Wells Fargo paid US$203 million to settle class-action litigation accusing the bank of imposing excessive overdraft fees on checking-account customers. Also in May, the New York attorney-general, Eric Schneiderman, announced a lawsuit against Wells Fargo over alleged violations of the national mortgage settlement, a US$25 billion deal struck between 49 state attorneys and the five largest mortgage servicers in the US. Schneidermann claimed Wells Fargo had violated rules over giving fair and timely serving.[70]

2015 Violation of New York credit card laws[edit]

In February 2015, Wells Fargo agreed to pay US$4 million for violations where an affiliate took interest in the homes of borrowers in exchange for opening credit card accounts for the homeowners. This is illegal according to New York credit card laws. There was a US$2 million penalty with the other US$2 million going towards restitution to customers.[109]

Executive compensation[edit]

With CEO John Stumpf being paid 473 times more than the median employee, Wells Fargo ranks number 33 among the S&P 500 companies for CEO—employee pay inequality. In October 2014, a Wells Fargo employee earning US$15 per hour emailed the CEO—copying 200,000 other employees—asking that all employees be given a US$10,000 per year raise taken from a portion of annual corporate profits to address wage stagnation and income inequality. After being contacted by the media, Wells Fargo responded that all employees receive “market competitive” pay and benefits significantly above US federal minimums.[110][111]

Tax avoidance and lobbying[edit]

In December 2011, the non-partisan organization Public Campaign criticized Wells Fargo for spending US$11 million on lobbying and not paying any taxes during 2008–2010, instead getting US$681 million in tax rebates, despite making a profit of US$49 billion, laying off 6,385 workers since 2008, and increasing executive pay by 180% to US$49.8 million in 2010 for its top five executives.[112] As of 2014 however, at an effective tax rate of 31.2% of its income, Wells Fargo is the fourth-largest payer of corporation tax in the US.[113]

Prison industry investment[edit]

The GEO Group, Inc., a multi-national provider of for-profit private prisons, received investments made by Wells Fargo mutual funds on behalf of clients, not investments made by Wells Fargo and Company, according to company statements.[114] By March 2012, its stake had grown to more than 4.4 million shares worth US$86.7 million.[115] As of November 2012, the latest SEC filings reveal that Wells Fargo has divested 33% of its dispositive holdings of GEO’s stock, which reduces Wells Fargo’s holdings to 4.98% of Geo Group’s common stock. By reducing its holdings to less than 5%, Wells Fargo will no longer be required to disclose some financial dealings with GEO.[116]

While a coalition of organizations, National People’s Action Campaign, has seen some success in pressuring Wells Fargo to divest from private prison companies like GEO Group, the company continues to make such investments.[117]

SEC settlement for insider trading case[edit]

In 2015, an analyst at Wells Fargo settled an insider trading case with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The former employee was charged with insider trading alongside an ex-Wells Fargo trader.[118] Sadis & Goldberg obtained a settlement that permitted the client to continue in securities industry, while neither admitting nor denying one charge of negligence-based § 17(a)(3) claim, and paying a US$75,000 civil penalty[119]

Wells Fargo fake accounts scandal[edit]

In September 2016, Wells Fargo was issued a combined total of US$185 million in fines for opening over 1.5 million checking and savings accounts and 500,000 credit cards on behalf of their customers, without their consent. The US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued US$100 million in fines, the largest in the agency’s five-year history, along with US$50 million in fines from the City and County of Los Angeles, and US$35 million in fines from the Office of Comptroller of the Currency.[120] The scandal was caused by an incentive-compensation program for employees to create new accounts. It led to the firing of nearly 5,300 employees and US$5 million being set aside for customer refunds on fees for accounts the customers never wanted.[121] Carrie Tolstedt, who headed the department, retired in July 2016 and received US$124.6 million in stock, options, and restricted Wells Fargo shares as a retirement package.[122][123]

On October 12, 2016, John Stumpf, the then Chairman and CEO, announced that he would be retiring amidst the controversies involving his company. It was announced by Wells Fargo that President and Chief Operating Officer Timothy J. Sloan would succeed, effective immediately. Following the scandal, applications for credit cards and checking accounts at the bank plummeted.[124] In response to the event, the Better Business Bureau dropped accreditation of the bank,[125] S&P Global Ratings lowered its outlook for Wells Fargo from stable to negative,[126] and several states and cities across the US ended business relations with the company.[127]

An investigation by the Wells Fargo board of directors, the report of which was released in April 2017, primarily blamed Stumpf, whom it said had not responded to evidence of wrongdoing in the consumer services division, and Tolstedt, who was said to have knowingly set impossible sales goals and refused to respond when subordinates disagreed with them.[128] The board chose to use a clawback clause in the retirement contracts of Stumpf and Tolstedt to recover US$75 million worth of cash and stock from the former executives.[128]

Wells Fargo reached a settlement with the United States Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission in February 2020. The settlement, which included a US$3 billion fine for the bank’s violations of criminal and civil law, does not prevent individual employees from being targets of future litigation.[129] Despite the 2020 stock market crash, Wells Fargo had to sell assets worth over $100 million in order to avoid future problems with the Federal Reserve. Previously, the Reserve had put a limit to Wells Fargo’s access to funds, as a result of the scandal.[130]

Racketeering lawsuit for mortgage appraisal overcharges[edit]

In November 2016, Wells Fargo agreed to pay US$50 million to settle a racketeering lawsuit in which the bank was accused of overcharging hundreds of thousands of homeowners for appraisals ordered after they defaulted on their mortgage loans. While banks are allowed to charge homeowners for such appraisals, Wells Fargo frequently charged homeowners US$95 to US$125 on appraisals for which the bank had been charged US$50 or less. The plaintiffs had sought triple damages under the U.S. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act on grounds that sending invoices and statements with fraudulently concealed fees constituted mail and wire fraud sufficient to allege racketeering.[131]

Dakota Access Pipeline investment[edit]

Wells Fargo is a lender on the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,172-mile-long (1,886 km) underground oil pipeline transport system in North Dakota. The pipeline has been controversial regarding its potential impact on the environment.[132]

In February 2017, Seattle, Washington‘s city council unanimously voted to not renew its contract with Wells Fargo “in a move that cites the bank’s role as a lender to the Dakota Access Pipeline project as well as its “creation of millions of bogus accounts.” and saying the bidding process for its next banking partner will involve “social responsibility.” The City Council of Davis, California, took a similar action voting unanimously to find a new bank to handle its accounts by the end of 2017.[133]

Failure to comply with document security requirements[edit]

In December 2016, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority fined Wells Fargo US$5.5 million for failing to store electronic documents in a “write once, read many” format, which makes it impossible to alter or destroy records after they are written.[134]

Connections to the gun industry and NRA[edit]

Wells Fargo is the top banker for US gun makers and the National Rifle Association (NRA). From December 2012 through February 2018 it reportedly helped two of the biggest firearms and ammunition companies obtain US$431.1 million in loans and bonds. It also created a US$28-million line of credit for the NRA and operates the organization’s primary accounts.[135]

In a March 2018 statement, Wells Fargo said, “Any solutions on how to address this epidemic will be complicated. This is why our company believes the best way to make progress on these issues is through the political and legislative process. … We plan to engage our customers that legally manufacture firearms and other stakeholders on what we can do together to promote better gun safety for our communities.” [135] Wells Fargo’s CEO subsequently said that the bank would provide its gun clients with feedback from employees and investors.[136]

Discrimination against female workers[edit]

In June 2018, about a dozen female Wells Fargo executives from the wealth management division met in Scottsdale, Arizona to discuss the minimal presence of women occupying senior roles within the company. The meeting, dubbed “the meeting of 12”, represented the majority of the regional managing directors, of which 12 out of 45 are women.[137] Wells Fargo had previously been investigating reports of gender bias in the division in the months leading up to the meeting.[138] The women reported that they had been turned down for top jobs despite their qualifications, and instead the roles were occupied by men.[138] There were also complaints against company president Jay Welker, who is also the head of the Wells Fargo wealth management division, due to his sexist statements regarding female employees. The female workers claimed that he called them “girls” and said that they “should be at home taking care of their children.”[138]

Auto insurance[edit]

On June 10, 2019, Wells Fargo settled a lawsuit for $385 million that was filed in 2017 concerning their customers and National General Insurance.[139]

Failure to Supervise Registered Representatives[edit]

On August 28, 2020, Wells Fargo entered into an agreement with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, in which Wells Fargo consented to the findings that it failed to reasonably supervise two of its registered representatives. These representatives allegedly recommended that investors invest a high percentage of their assets in high-risk energy securities. Wells Fargo consented to a fine of $350,000 as well as restitution payments to its investors.[140]

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_comments _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default”][/et_pb_comments][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section][et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default” custom_padding=”0px||39px|||”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.9.3″ _module_preset=”default”][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]